INDIA GREENS PARTY

(India Greens Party is registered with the Election Commission of India under Section 29A of the Representation of the People Act, 1951. Registration Number: 56/476/2018-19/PPS-I, effective from 18/07/2019.)

National Head Office: GreenDham AnandiChait, IndraBalbhadra Parisar, Unchir-Dunktok, SH-31, PO-Ghurdauri, Distt-Pauri Garhwal, Uttarakhand, INDIA. PIN-246194.

Email: contact@indiagreensparty.org Website: https://indiagreensparty.org

………………………

iGP opposes reclassification of forest areas; exemptions for projects near border areas; exemptions for zoos, safari parks and ecotourism activities, and disempowering local communities as proposed in the Forest Conservation (Amendment) Bill, 2023.

23 August 2023

To

Shri Narendra Modi

Hon’ble Prime Minister, Government of India

New Delhi, INDIA.

Hon’ble Prime Minister Sir,

Greetings from the India Greens party!

The India Greens Party (iGP) is a pan-India Green political party, registered with the Election Commission of India. We are committed to raising political awareness about the issues related to ecological wisdom, sustainability, social justice, participatory democracy, nonviolence and respect for diversity.

Hon’ble Prime Minister Sir, as you know well, the Forest Conservation (Amendment) Bill 2023 was introduced in the Lok Sabha in March this year, and now it is awaiting debate in the Rajya Sabha after having been passed by the Lok Sabha with almost no debate in June this year (2023). The Bill was referred to a Joint Parliamentary Committee (JPC) comprising 32 members from both Houses of Parliament and across party lines. Rajendra Agrawal, the Bharatiya Janata Party MP, was the Chairperson of the JPC.

The Bill was not referred to the relevant Parliamentary Standing Committee, which in this case would have been the Standing Committee on Science and Technology, Environment, Forests and Climate Change, headed by Congress MP Jairam Ramesh. As per the Pre-legislative Consultation Policy, it is considered good practice – though not mandatory – to refer Bills to Standing Committees for review. But the government bypassed this oversight function in the case of the Forest (Conservation) Amendment Bill 2023. Besides, the JPC did not propose a single change to the Bill in its report despite receiving around 1,200 representations – including objections from tribal groups, conservationists, environmental lawyers, activists, and citizen groups. Six members of the JPC itself wrote dissent notes.

Sir, the Bill got a free pass in the Lok Sabha as most Opposition MPs were focused on highlighting the violence in Manipur. It was set to be debated in the upper house at the time this article went to press. Debate or no, the Bill’s drastic break from the longstanding legal definition of ‘forests’, its focus on creating carbon sinks (instead of the Act’s aim to conserve existing forests), and the uncertainty over its coverage don’t bode well.

It is in this context that the India Greens Party is deeply concerned about the government’s Forest Conservation (Amendment) Bill. With only 21 per cent of India’s land area having forest cover and even more worryingly, only 12.37 per cent intact natural forest, we have a long way to go to meet our target of 33 per cent forest cover.

Broadly, the Bill seeks:

- to restrict the conservation scope of the Act to only certain forest lands;

- to exempt border lands from the obligation to seek permissions to clear forests in order to construct “strategic linear projects of national importance”; and

- to allow some non-forest activities on forest lands, like running zoos and ‘eco-tourism’ facilities.

Therefore, in this Petition, we demand your attention to the following points:

- The Bill’s principal thrust is that it redefines what a ‘forest’ is in Indian law. It stipulates that only those lands that were notified as ‘forest’ under the Indian Forest Act 1927, any other relevant law or were recorded as ‘forests’ in government records will be acknowledged as ‘forests’ under the Act as well. This revision stands in stark contrast to the wide applicability of the extant Act at present – i.e., it applies to “any forest land”. A Supreme Court judgement in 1996 had reiterated such a broad application. It said, inter alia, that a ‘forest’ includes all land recorded as such in government records regardless of ownership as well as “deemed forests”, which are not officially classified as ‘forests’ but satisfy the dictionary meaning of the word: any large area with significant tree cover and undergrowth.

- The Supreme Court had asked States to undertake an exercise to identify and notify their own deemed forests. But even after almost 30 years, many states are yet to complete this exercise. In cases where they have, we don’t know how scientific the process of identification was. As such, the amendment opens up all land that hasn’t been officially classified as ‘forests’ to commercial activity. It also removes the checks and balances the Act currently includes, in the form of forest clearance permissions and the informed consent of the local community.

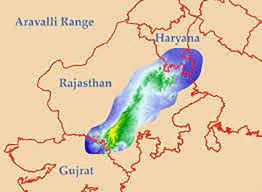

- The areas that stand to be affected in a significant way include about 40% of the Aravalli range and 95% of the Niyamgiri hill range; the latter is home to the Dongria Kondh, a Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group. Many experts are also uncertain, and thus apprehensive, about the actual extent of land that will fall outside the purview of the amended Act considering the State-wise data of deemed forests is not publicly available.

- The Bill seeks to exempt linear infrastructure projects – like roads and highways – from seeking forest clearance permissions if they are located within 100 km of the national border. Experts have raised concerns because “strategic linear projects of national importance” is an undefined term and can thus be misused to push through infrastructure projects that are devastating for the local ecology. This is of particular concern in the Northeastern States, where the exemption would apply de facto almost across the region. Many BJP-ruled states in the region disputed the 100-km exemption during the JPC’s consultation process. On the one hand, Nagaland asked for a variable distance for exemption, given its small size and location within the Indo-Burma biodiversity hotspot, and Tripura wanted it to be reduced to 10 km. On the other, Arunachal Pradesh asked for the range to be increased to 150 km.

- The Ministry of Tribal Affairs also raised concerns with the JPC about the amendment’s implications on community rights enshrined in the Forest Rights Act 2006, according to the final JPC report. A document shows that, during consultations, the JPC accepted the Union Environment Ministry’s inadequate justifications for the proposed amendments and even responses that were not related to the question that had been asked, raising concerns about the integrity of the parliamentary process.

- At least from the early 1970s, there has been a growing realisation of both the environmental damage that humans are collectively causing and the impact this is having on our lives. For example, extensive wildfires, prolonged and intense heat waves, extreme rainfall events, powerful and more frequent cyclones, rampant loss of biodiversity and the unravelling of ecosystems have all, and in many cases synergistically, impacted the lives of billions of people. Premature deaths, increasing incidence of diseases, destruction of built infrastructure, declining soil fertility, and decreasing quality of air and water are a short list of the impacts we are suffering. Globally, the response has included dozens of multilateral environmental agreements committing to the time-bound reversal of these trends. Many countries, especially India, have put in place strong policies and laws to protect the environment and restore it.

- The most biodiversity-rich part of the country, the northeastern states, show a net decline of 3,199 sq km of forest cover from 2009-2019 and much of the marginal increase in forest cover is in the form of commercial plantations and urban parks. These cannot replace the ecological functions performed by intact natural ecosystems.

- The Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980 along with the Supreme Court’s 1996 order in TN Godavarman vs Union of India have provided a strong basis for the protection of natural ecosystems. What is required is better and more effective implementation. Why try to fix something that is not broken? Especially when this legal framework has served us well.

- The India Greens party opposes the reclassification of forest areas; exemptions for projects near border areas and for security purposes; exemptions for zoos, safari parks and ecotourism activities, and disempowering local communities.

- By stating that the Forest Conservation Act (FCA) will only apply to areas recorded as “forest” in government records, as on or after October 25, 1980, we fear that the amendment will invalidate the SC’s 1996 judgment in TN Godavarman. The Court has interpreted the meaning of forest as its dictionary definition, expanding the purview of the FCA over all forests and not restricting it to only officially declared tracts. If these areas are declassified, it will result in thousands of sq km of forests losing legal protection. The scale of the potential disaster is humungous, as 1,97,159 sq km of our forests lie outside Recorded Forest Areas, implying that 27.62 per cent of our total forest cover of 7,13,789 sq km is at risk of losing legal protection.

- We are also concerned because it is proposed to remove the necessity of forest clearances for security-related infrastructure within 100 km of international borders. These areas are home to some of the most ecologically important ecosystems, including the forests of the Northeast, the high-altitude deserts of Ladakh and Spiti, the alpine forests and grasslands of Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh, and the open scrub and desert ecosystems in the west.

- While recognising the need for military security, it is equally if not more important to recognise that ecological security is a critical part of national security and central to the well-being of our citizens. Hence, the need for fast-tracking should not result in the complete elimination of the need for environmental appraisal and taking informed and balanced decisions. The natural ecosystems play a crucial role in buffering against increasingly unpredictable weather patterns caused by climate change. The loss of natural ecosystems will result in greater human displacement and heightened internal security risks. A zoo or a safari park is not a forest.

- Natural ecosystems are complex functional units and once destroyed, it is very difficult to restore them. Science is still trying to understand how this actually functions. Zoos and safari parks are built by humans with the objectives of ex-situ conservation, education and recreation. It is absolutely inappropriate to clear and by implication destroy natural ecosystems to build them.

- Instead, we should aim to establish science-based and world-class conservation centres away from forested sites. While eco-tourism can be an important ancillary activity to generate employment, it is not correct to exempt it from clearances as it indicates that tourism will take priority over nature. In many cases, ecotourism projects have resulted in large-scale construction, which has negatively impacted natural ecosystems.

- A provision allowing the central government to exempt clearance for “any other purposes”, could have disastrous consequences, as this could open the door to a whole host of activities on forest land that will no longer require clearances.

With Green wishes,

(Suresh Nautiyal)

Founder, Patron, Mentor & Chief Spokesperson

iGP — India Greens Party.

Website: www.indiagreensparty.org

Mobile phone: +91-8860072030.

You must be logged in to post a comment.